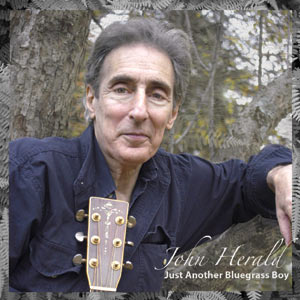

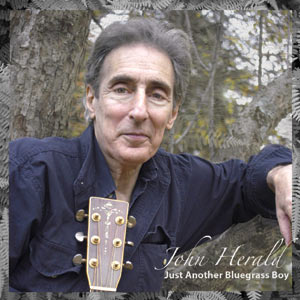

John Herald

Just Another Bluegrass

Boy

(2005)

| "I have never

stopped writing songs because when you get towards

the end and you know that it's going to be a finished song it's very

exciting, one of the most thrilling things that can be done and one of

the most artistic things you can do as a

musician..." |

|

|

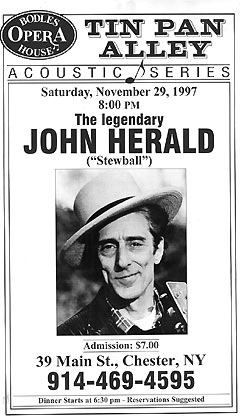

John said he had to work hard at writing songs. And his performances

were so dynamic, so electrifying, that he always thought he had to

give that same sort of thing on record. It was only toward what

turned out to be the end of his days that he could be convinced and

cajoled into the confidence to put out this set of him singing only

his own songs. But for those who knew him and his music, this was the

record we all wanted him to do. And, it really wasn't a new idea to

him. Indeed, he had been planning the project over a number of years,

gathering the recordings from the sessions that he liked, sorting

through the songs he wanted to present. John died before it was

finished, though. And thus it fell to those of us who were helping

him to make the final choices and get it done.

|

Listen to Samples

|

Jon the Generator |

|

Hats Off to the Cajun Moon |

|

Working It Out By Walking It Off |

|

|

But John also wanted the chance to tell some of his story.

Oh I thought that when I left my home I was a man of some reknown

But in old New York I was on the walk,

Just an ordinary fool from a one horse town,

just another bluegrass boy

Despite those lyrics, John Herald was not a fool from a one horse town. He was a New Yorker.

Let's just let him tell it.

"I'll just start from the beginning," said John, in about four hours

of interview we did for these pages.

"I was born in 1939 on Grove Street in Greenwich village. My father

was a bohemian poet, Leon Serabian Herald. You wouldn't know him

unless you looked in literary magazines of the 20s, 30s and 40s, he

was published in all the periodicals of the day. So he had a lot of

colorful characters around the house, poets, painters, sculptors.

Kenneth Fearing, who was considered one of the Village top of the line

bohemian poets, was my father's best friend and he lived about four

blocks from us. My mother died when I was three and after she died it

took the inspiration away from my father's poetry. From three to

eight - five years - I was in five different foster homes. But if I

expressed any unhappiness, my father would take me out. When I was

nine, I went to a progressive boarding school, started by a fellow

named Scott Nearing, who wrote books about the back to the Earth

movement.

"We moved to the east border of Greenwich Village. We lived on 13th

Street and 3rd Avenue. That's where life started getting really

interesting. We lived on the third floor. At the time it was the

Bowery we lived on. There was nothing there but bar, bar, bar, pawn

shop, pawn shop, flop house, flop house. They had an elevated train

which ran the length of the third floor where we lived. So I could

see into the trains. Because of the Third Avenue el, it made it kind

of dark. It was not that far from the second world war and there were

a lot of places where derelicts went to drink, Bowery places.

"One day, when I was 16, my father took me to Washington Square Park

on a Sunday. For a few years before that they would allow folksingers

and bluegrass singers to pick in Washington Square Park from noon to

six at night. I would go down there and meet a couple of friends from

camps where I went in the summer.

"Pete Seeger had come to one camp, Woodland, which is up in Phoenicia.

He said, well I don't care if you can't carry a tune with a

wheelbarrow, just let loose and you might be singing in a harmony, it

doesn't matter. I didn't know much about folk music at the time. I'd

heard about it, my father had taken me to different functions at which

I'd heard Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie.

"Pete Seeger had come to one camp, Woodland, which is up in Phoenicia.

He said, well I don't care if you can't carry a tune with a

wheelbarrow, just let loose and you might be singing in a harmony, it

doesn't matter. I didn't know much about folk music at the time. I'd

heard about it, my father had taken me to different functions at which

I'd heard Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie.

"Pete was trying to get us to sing, but finally we did start singing

and I heard my voice sort of soaring above everybody else, I had a

really high voice and it was like a thrill. And that's where I found

out that I just love singing, it was like an epiphany. I didn't know

if I was a good or bad singer, I just knew it was fun.

"So at Washington Square, one of the first people I saw after I

started going there by myself was a fellow named Roger Sprung, a very

imposing fellow. Extremely tall and my friends from camp kept nudging

me to ask Roger if I could sing a song. Finally after about two or

three Sundays I worked up enough nerve, and he said 'well, can you

sing, kid?' and I said well I really don't know, so he didn't say

anything, and finally he said, well you want to try a song? I said,

yeah but I was very timid. So I started singing and I got through and

he said, hm, not bad. And then he waited a few more songs and asked

me to sing again. Then I started coming down and he was on me all the

time and he wanted me to be the lead singer in his coterie around

Washington Square.

"I'd see people down there that we know today, here in Woodstock,

Happy Traum, Eric Weissberg. Eric used to play with a fellow named

Marshall Brickman, who co-wrote movies with Woody Allen. And just by

chance I happened to go to the University of Wisconsin, unbeknownst to

me, with Eric Weissberg and Marshall Brickman. On my first day there,

I went to a freshman mixer, and Eric was walking out and I see him and

say, golly are you Eric. And he said yeah, and I said, I've been

watching you in Washington Square Park. He said really? Do you like

bluegrass? So we got over to his place and he handed me a guitar and

I said I don't play, I just love the music and can sing it a little

bit. At the end of the year, Eric showed me a couple of guitar

chords.

"So I went back home and persuaded my father to give me $30 for a

guitar. There was nothing but pawn shops where we lived and they had

every kind of guitar imaginable, from every country imaginable. You'd

go in and they had maybe 100 guitars. So I picked out a nice little

Gibson, not knowing anything about brand names, it looked nice and

sounded real nice. So I bought this guitar, took it home, played a

couple of guitar chords and it sent shivers up and down my spine and I

said, well that's the end of my schooling, I'm going to become a

guitar player. I knew my father was not going to be happy, but he

didn't come down on me hard, which was kind of surprising."

"So we started playing at Washington Square and we would get crowds

sometimes 15 people deep around us, so we knew that we were liked.

The second summer, when we were just deciding that we would form a

group, Eric Weissberg's mother came up with a name, The Greenbriar

Boys, which was quite catchy. A guy came up to us and said he was

from Vanguard Records and would give us a call to record. And we said

to ourselves, yeah, sure. But lo and behold, Maynard Solomon gave us

a call and we recorded on a quarter of a record, called New Folks and

Joan Baez somehow heard of it. We're talking 1957. By 1958, Solomon

wanted us to record our own record and Joan Baez heard that and wanted

us to record with her. So we recorded two songs with her on her

second album and then she wanted us to tour with her. So we went from

totally unknown in one year to playing in front of thousands of

people. We all loved her. To this day, I love her."

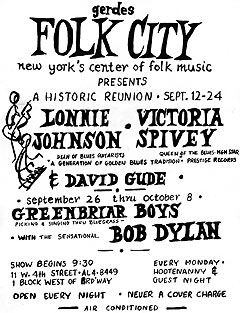

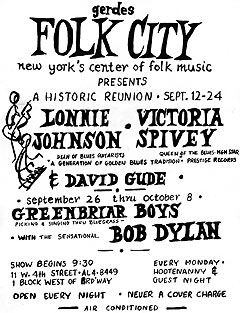

One story of John's at that time concerned Bob Dylan's famous review

in the New York Times, written by Robert Shelton, one of the key

launching points of his career. Seems Dylan was the opening act that

night for the Greenbriar Boys at Gerde's Folk City. The Greenbriar

Boys were asked if it was OK for Dylan to open their show.

One story of John's at that time concerned Bob Dylan's famous review

in the New York Times, written by Robert Shelton, one of the key

launching points of his career. Seems Dylan was the opening act that

night for the Greenbriar Boys at Gerde's Folk City. The Greenbriar

Boys were asked if it was OK for Dylan to open their show.

"By this time, Bob was a friend of mine, so I said fine. I wish he

would return the favor now. We could have said no to Dylan, but Dylan

would have ended up playing there with somebody. I liked Dylan quite

a bit, so that's how that happened. Anyway, Robert Shelton was the

critic for the New York Times, wrote an amazing review of Dylan saying

that Dylan was essentially going to be a star, going to go shooting

straight up from there, from Folk City."

Dylan has, in fact, visited John in Woodstock within the last decade,

to swap songs.

The Greenbriar Boys recorded three albums by themselves on Vanguard,

one on which they backed up singer Dian James, on Elecktra Records, as

well as on a 1959 collection called New Folks. In 1972, Vanguard put

out a Best of the Greenbriar Boys. The group went through personnel

changes, having included at various times Eric Weissberg, Bob Yellin

and Ralph Rinzler, Frank Wakefield. The band with Yellin and

Weissberg became the first touring bluegrass band made up of

northeastern people. They played the big folk festivals, Newport and

such, played on the Grand Ole Opry as substitutes for Flatt and

Scruggs, played at Union Grove, where they were introduced as the Jews

from New York; they toured with Johnny Cash, the Louvin Brothers and

Jim Reeves.

The group broke up in 1966, but The Greenbriar Boys, John, Yellin, and

Weissberg have done tours every 12 to 15 years since, playing the

Philadelphia Folk Festival, Champlain Valley Folk Festival and the

Lincoln Center Folk Festival.

And now I swim ashore, for I must make it

Although I'm up to my neck

In high muddy water

"I was introduced to Woodstock at the age of three. When my mother

was alive, they would come up and visit the Downers on Zena road.

When I got to be around 19 or 20 I would come to Woodstock and camp

out, maybe with a girlfriend. At 22 I started renting a cabin in the

summer and then I met a native lady and we got married, Kim Chalmers

Herald. The marriage lasted about six years." John and Kim remained

close friends, though, throughout his life.

"After the Greenbriar Boys broke up, I knew the folk song writers in

New York, the guys who played poker up above the Gaslight, and though

I'd come up to Woodstock and become a songwriter.

"When I was married we lived down on Hasbrouk Lane and I became

friends with Jerry Jeff Walker, who became big and moved to Lubbock

Texas, which is a place where Willie Nelson and a certain coterie of

folksinging cowboys became part of that crowd. Townes Van Zandt,

Waylon Jennings. We used to wake up sometimes and Jerry Jeff would be

sleeping out on our porch, he was a guy who sort of wanted to live a

life like Woody Guthrie and Jack Elliot. Just had a little bedroll

and backpack and travel all over. We just had some parties, sat

around campfires until late at night..."

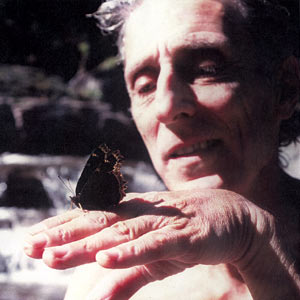

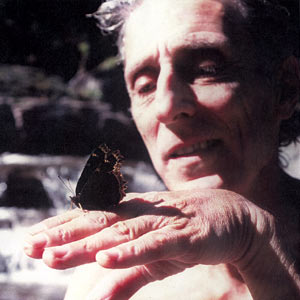

"The thing I like most about Woodstock, to this day, is the

surroundings. If I hadn't become a musician I would have been

something in the wild world, the naturalist world. I majored at

entomology at the University of Wisconsin. I moved to Woodstock and

became what I call a forage ranger. I know a lot about eating and

hunting for wild plants. And then became an amateur mycologist and

mycophagist, one who specialized in eating mushrooms. One that goes

hunting wild edible mushrooms, 50 different kinds. So I really lived

for the summers because I know all the best swimming holes and follow

all the streams for miles around. I go swimming at one of the towns

up near here but I won't name it, but there'll be hundreds of trout

all around your heads, you might be diving off a reef. And that is my

big love for Woodstock to this day."

A fire in 1969 destroyed his house and possessions. A couple of years

in California ensued, where a reconstituted Greenbriar Boys once even

included Jerry Garcia on banjo, a meeting with Michael Nesmith, whose

song Different Drum was reworked and recorded by John, and made into

the first hit for Linda Ronstadt's band, The Stone Poneys. She

followed that with the Greenbriar's Up To My Neck In High Muddy Water,

but it wasn't the same kind of hit.

Roll on John

And make your time

Cause I'm broke down

And I can't make mine

John came back to Woodstock, "hoping to become another Bob

Dylan and found out that I was not a songwriter, that I had to work

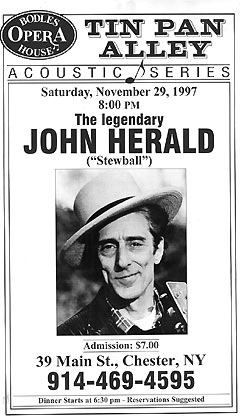

very hard at it. But I have never stopped writing songs because when

you get towards the end and you know that it's going to be a finished

song it's very exciting, one of the most thrilling things that can be

done and one of the most artistic things you can do as a musician,

writing your own music. And I've gotten a little action with that,

mostly through the song Stewball that Joan Baez and Peter Paul and

Mary recorded. And Jon the Generator, which Maria Muldaur recorded.

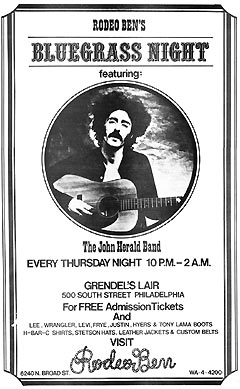

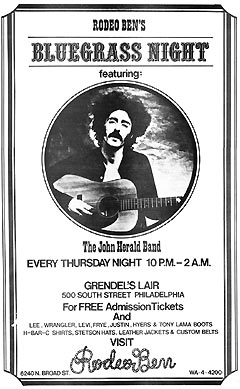

"Since then, I've had my own band called the John Herald Band, an

electric band for a while. I was lucky enough to train some people

who are much more famous than myself, including Larry Campbell, who's

been with Dylan, Cindy Cashdollar who's now getting very famous as a

lap steel and Dobro player, Gordon Titcomb, who's had a lot to do with

Arlo Guthrie and Paul Simon, I don't know exactly what. I believe I

was the first working band that they were in."

John came back to Woodstock, "hoping to become another Bob

Dylan and found out that I was not a songwriter, that I had to work

very hard at it. But I have never stopped writing songs because when

you get towards the end and you know that it's going to be a finished

song it's very exciting, one of the most thrilling things that can be

done and one of the most artistic things you can do as a musician,

writing your own music. And I've gotten a little action with that,

mostly through the song Stewball that Joan Baez and Peter Paul and

Mary recorded. And Jon the Generator, which Maria Muldaur recorded.

"Since then, I've had my own band called the John Herald Band, an

electric band for a while. I was lucky enough to train some people

who are much more famous than myself, including Larry Campbell, who's

been with Dylan, Cindy Cashdollar who's now getting very famous as a

lap steel and Dobro player, Gordon Titcomb, who's had a lot to do with

Arlo Guthrie and Paul Simon, I don't know exactly what. I believe I

was the first working band that they were in."

Three solo albums and a couple of John Herald Band recordings have

been released over the years and John continued to play in New York

City at the Parkside Lounge on Houston Street and has been a charter

member in the Woodstock Mountain Review, the large local collection

that includes Happy Traum, Bill Keith, Artie Traum, Jim Rooney, Roly

Salley, Cindy Cashdollar, Pat Alger, Eric Kaz and others. He even did

a stint as a country music disc jockey on WDST radio in 1980.

The John Herald Band "played most of the major folk festivals, and

quite a few bluegrass festivals. And this was the time I had the

longest band I ever had, consisted of Caroline Dutton on fiddle, Cindy

Cashdollar on Dobro, George Quinn on bass, and assorted banjo players,

Joe Deetz and another named Joe Val. Now, I have a band, but I don't

always use the exact same musicians. But I use the best musicians in

the northeast."

John had a lot of stories he had hoped to tell, reams of notes about

things like the time Chuck Berry told him how he loved Bill Monroe's

music, and that's how he wrote Memphis…or what he called the 'Garden

of Eden fun' of the Ashokan Clog and square dances where 15 to 35

people would get naked in the sauna and sing the Everly Brothers' Bye

Bye Love…or how he sold mushrooms he hunted to restaurants and

stores…or how the Greenbriar Boys boycotted Hootenanny television show

along with Dave Van Ronk, Billy Faier and Tom Paxton to protest that

the show wouldn't have Pete Seeger as a guest, and how the story was

on the cover of Billboard…or his short stint in the band The Flying

Machine, with James Taylor…about how Ralph Rinzler discovered Clarence

Ashley and Doc Watson and he used to stay with the Watsons when he was

in North Carolina…how he loved the guitar playing of Riley Puckett,

who played with Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers, and Arthur 'Guitar

Boogie' Smith…how he split the bill at the Gaslight with Bill

Cosby…how his great, great great great grandfather was John Greenleaf

Whittier…

The fame that John Herald sought did not ever materialize, but he

never gave an inch, never compromised a morsel for anyone. "I always

thought I was a little too folky for bluegrassers and a little too

bluegrassy for folk fans," he said. But it wasn't fame for fame's

sake, it was to share the joy of performing, the fruits of his hard

won songwriting, and the charm of his warm heart.

If ever by chance I should see you again

I won't pretend that I'm over you yet

I'll just reach out and touch you

In a way that you'll know

You're someone I'll never forget

Notes on the songs:

Bluegrass Boy

Bluegrass Boy

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Gordon Titcomb, mandolin;

Roly Salley,

bass; John Sebastian, harmonica and vocal; Happy Traum, melodica; Andy

Robinson, vocals. Recorded 1977 at Bearsville Sound Studio, produced

by George James, Artie Traum, Happy Traum.)

John always said that he'd never sing this song as well again as on this recording, which

first appeared on the album Woodstock Mountains: More Music From Mud Acres. I'm sure people have different ideas when they think of John, but for me, this is always the song that pops into my head first. It flows so smoothly that you don't realize how beautifully crafted the song is, its slow descent down the guitar fingerboard drawing you in close for the payoff.

John also wanted to acknowledge a debt to Uncle Dave Macon on this song.

Single Life

(John Herald, lead and rhythm guitar, vocal; Rob Stein, lead

guitar; Mindy Jostyn, concertina. Recorded mid-1990s at Bearsville

Studio, Mark McKenna, engineer.)

John went through a lot of titles for this song of loneliness and

longing, never quite being satisfied with its name until relatively

recently.

Moneyland

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Rob Stein, guitar; Mindy Jostyn,

banjomandolin

Recorded mid-1990s at Bearsville Studio, Mark McKenna, engineer.)

The sharp political edge on this song reflects John's identification

the have-nots of the world who struggle to earn a living, and

sometimes rise up to fight the power. George Quinn said it best - "He

wanted to go back to America in the 1930s. The era of the Great

Depression and union activism. He was from the Pete Seeger school of

music - justice songs, anti-corporate, Worker's parties…"

You can buy a judge or a bribe or a thug or a bomb or a shredding

machine

You can buy your way through or into and onto any ticket or TV

machine,

it's a money disease

It's a thing called greed; and it feeds on those who need the money most in Moneyland

Hats Off To The Cajun Moon

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Greg Garing, mandolin, fiddle; Eric

Weissberg, bass. Recorded mid-1990s at Bearsville Studio, Mark

McKenna, engineer.)

Just beautiful.

In the mid 1990s, Sally Grossman gave John some time in the Bearsville Studios, with Mark McKenna and Chris Laidlaw engineering. And Charles Lyonhart helped with the production. Those sessions make at least half of this album.

Working It Out By Walking It Off

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Bill Keith, banjo; Jay Ungar, fiddle;

Brian Hollander, Dobro; George Quinn, bass. Recorded June, 2005,

Nevessa Studio, Woodstock)

Cut at John's last recording session where he sounded as good as ever.

The most bluegrass-sounding tune on the CD, featuring beautiful work

from the great Bill Keith on banjo and Jay Ungar on fiddle, it also

features some of John's soaring vocal swoops and yodels.

Still Got It Bad

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Cindy Cashdollar, Dobro; Caroline

Dutton, fiddle; George Quinn, bass. Recorded live at Joyous Lake,

Woodstock, May 26, 1983, by Chris Andersen in Nevessa Remote Truck No.

1)

A long, live night at the Lake in 1983 yielded a release called Bring

It On Down To My House, that had life as a cassette but never made it

to the CD era. This was the classic John Herald Band, unelectricfied

version, with Cindy Cashdollar and Caroline Dutton teaming with John

and George Quinn. Joe Deetz was the banjo player in the band on the

album. But this song, one of John's most lovely aching ballads, had

no banjo.

The Bond

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Eric Weissberg, Dobro; Greg Garing,

Fiddle; Trip Henderson, harmonica; George Quinn, bass. Recorded

mid-1990s at Bearsville Studio, Mark McKenna, engineer.)

This one is for Charles.

Don'cha Cadillac Me

Don'cha Cadillac Me

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Jay Ungar, mandolin; George Quinn, bass

Recorded June, 2005, Nevessa Studio, Woodstock)

Written as it is sung here, John was nervous that General Motors would

land an SUV on his head for denigrating their flagship. So he cut

various versions in which he'd substitute 'limousine' for Cadillac.

But nothing works so well as a Cadillac...y'hear that General

Motors…

Martha (The Last Passenger Pigeon On Earth)

(John Herald; guitar, vocal; Cindy Cashdollar, Dobro; Caroline

Dutton, fiddle; George Quinn, bass.

Recorded live at Joyous Lake, Woodstock, May 26, 1983.)

John's Tour de Force, tying history, emotion, metaphor into this

compelling tale. Yes, John, a piece of us all does go with you…

Queen Of Spoons

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Rob Stein, guitar

Recorded mid-1990s at Bearsville Studio, Mark McKenna, engineer.)

Who was she?

Flock Of Flamingos

(John Herald, guitar and vocal; Trip Henderson, harmonica; George

Quinn, bass

Recorded mid-1990s at Bearsville Studio, Mark McKenna, engineer.)

Sort of 'Blues in a Bottle' turned upside down. Trip's harp and

John's great guitar solo propel this one along.

Special Magic

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Jay Ungar, fiddle; Guy 'Fooch' Fishetti,

fiddle; George Quinn, bass. Recorded June, 2005, Nevessa Studio,

Woodstock)

Jay Ungar and Fooch provide a lush double-fiddle cushion for John's

remembrance of a love that had it.

Jon The Generator

(John Herald, guitar, vocal; Cindy Cashdollar, Dobro; Caroline

Dutton, Fiddle, Charlie Sayles, harmonica; Joe Deetz, banjo; George

Quinn, bass Recorded live at Joyous Lake, Woodstock, May 26, 1983.)

John reworked and rewrote the Blind Willie Johnson call-and-response spiritual because he couldn't find the words. It became his own classic, dangling audie nces with its electricity and ultimately expressing a great optimism, reminding us how People don't like the habit, Of mistrusting each other

This doesn't have to be the last John Herald album. There is much

more material that can be culled and shaped into future projects. But

for now, this one will have to do. Here's to you, John.

Brian Hollander

Woodstock, New York

August, 2005

Produced by John Herald and Brian Hollander for Sam Hood Management

Design: Megan Denver

Production: Tod Levine, Magnetic North

Disc mastering: Tom Mark, Make Believe Ballroom

Photos by Holly Wilmeth

Special thanks to Robbie Dupree, Artie Traum, Kurt Henry, Charles

Lyonhart, Diane Chetta, Dan Schneider, John Sebastian, Charlotte Pfal,

Happy Traum, Steve Stiert, Jay Ungar, George Quinn, Kim Chalmers

Herald and the Thursday Committee.

"Pete Seeger had come to one camp, Woodland, which is up in Phoenicia.

He said, well I don't care if you can't carry a tune with a

wheelbarrow, just let loose and you might be singing in a harmony, it

doesn't matter. I didn't know much about folk music at the time. I'd

heard about it, my father had taken me to different functions at which

I'd heard Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie.

"Pete Seeger had come to one camp, Woodland, which is up in Phoenicia.

He said, well I don't care if you can't carry a tune with a

wheelbarrow, just let loose and you might be singing in a harmony, it

doesn't matter. I didn't know much about folk music at the time. I'd

heard about it, my father had taken me to different functions at which

I'd heard Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie.

John came back to Woodstock, "hoping to become another Bob

Dylan and found out that I was not a songwriter, that I had to work

very hard at it. But I have never stopped writing songs because when

you get towards the end and you know that it's going to be a finished

song it's very exciting, one of the most thrilling things that can be

done and one of the most artistic things you can do as a musician,

writing your own music. And I've gotten a little action with that,

mostly through the song Stewball that Joan Baez and Peter Paul and

Mary recorded. And Jon the Generator, which Maria Muldaur recorded.

"Since then, I've had my own band called the John Herald Band, an

electric band for a while. I was lucky enough to train some people

who are much more famous than myself, including Larry Campbell, who's

been with Dylan, Cindy Cashdollar who's now getting very famous as a

lap steel and Dobro player, Gordon Titcomb, who's had a lot to do with

Arlo Guthrie and Paul Simon, I don't know exactly what. I believe I

was the first working band that they were in."

John came back to Woodstock, "hoping to become another Bob

Dylan and found out that I was not a songwriter, that I had to work

very hard at it. But I have never stopped writing songs because when

you get towards the end and you know that it's going to be a finished

song it's very exciting, one of the most thrilling things that can be

done and one of the most artistic things you can do as a musician,

writing your own music. And I've gotten a little action with that,

mostly through the song Stewball that Joan Baez and Peter Paul and

Mary recorded. And Jon the Generator, which Maria Muldaur recorded.

"Since then, I've had my own band called the John Herald Band, an

electric band for a while. I was lucky enough to train some people

who are much more famous than myself, including Larry Campbell, who's

been with Dylan, Cindy Cashdollar who's now getting very famous as a

lap steel and Dobro player, Gordon Titcomb, who's had a lot to do with

Arlo Guthrie and Paul Simon, I don't know exactly what. I believe I

was the first working band that they were in."

Bluegrass Boy

Bluegrass Boy

Don'cha Cadillac Me

Don'cha Cadillac Me